Art and Technology, different twins.

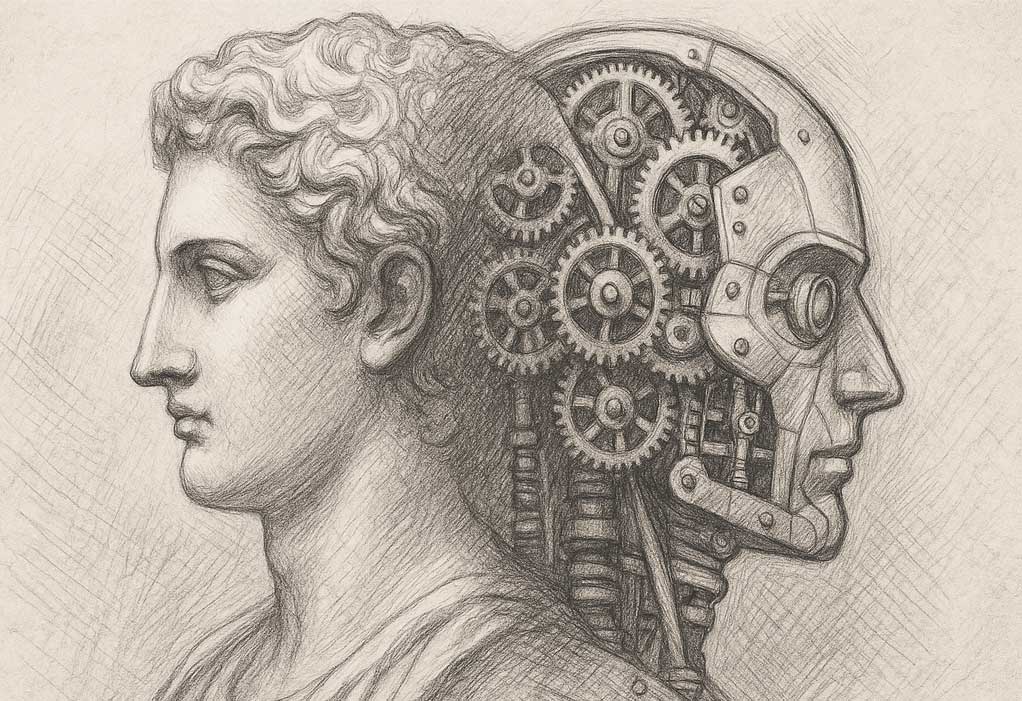

A blog about the true family relationship between the two fundamental structures on which the human mind rests.

by Daniele Lunghini

4- The coin of Diana Gabaldon

Diana Gabaldon is the author of Outlander, the novel – and later the television series – that has become a cultural phenomenon in recent years. Although the story doesn’t revolve around scientific themes but rather historical ones, it does contain one central element that brushes up against the scientific: time travel.

What many don’t know is that Gabaldon’s background is anything but literary. She is an expert in numerical analysis and database design, and she has written articles and reviews for major national computer magazines such as Byte, PC Magazine, and InfoWorld.

Why, then, bring up Diana Gabaldon in a conversation about art and technology – and about how these two dimensions are close, intertwined, almost Siamese in their empathy and symbiosis?

Because in this talk, Gabaldon makes it remarkably clear that art and technology are, at their core, two sides of the same coin.

She explains:

“People often ask me how I went from being a scientist with all these degrees to becoming a novelist. What they really mean is that science seems cold, clinical, orderly, while creativity is supposed to be bright and colorful.

But science and art are two sides of the same coin. They’re both based on the same ability: perceiving patterns and extracting them from chaos.

When you do science, you define your chaos by choosing a subject, and within that subject you try to identify patterns and explain them to others. The same thing happens when you write a novel: you define your chaos through the theme or genre, and you also weave in your own inner chaos. You look for equivalent patterns.

In science you formulate a hypothesis: ‘I think this is what’s happening in my system,’ and then you try to support it through experimentation. Your novel is your hypothesis, and your experiment is the audience.”

This perspective shines a light on the objective structures within art – in this case, storytelling – and on their surprising resemblance to the processes of science and, by extension, technology.

Chaos and Hypothesis.

These are the two foundational elements shared by both systems.

Chaos generates the need for order; hypothesis generates the need for experimentation and for the development of possible scenarios. Experimentation and the creation of models are the common steps that lead both processes toward completion.

In science and technology, chaos is the starting point: it is what must be translated into workable frameworks so that it can become a tool, a solution, or a form of progress.

In art, by contrast, chaos becomes a narrative magnet: an intriguing knot of meaning toward which the mind feels irresistibly drawn.

And so we can say that art and technology, each in its own way, help repair the faulty parts of our lives.

Art gives us the illusion – and the comfort – of emotional order, offering a way to give meaning to our personal struggles.

Technology, for its part, promises a more manageable world, turning the forces of nature into solvable problems through a few mechanisms.

This is why, as Gabaldon suggests, art and technology truly are “two sides of the same coin”: one seeks to understand the world, the other seeks to interpret it.

But both arise from the same primordial impulse: to give shape to what, at the beginning, has no shape at all.

3- The secret revealed

From the painted stick in the cave to the illuminated codes of the monastery, the thread is clear: art asks the questions and technology turns them into tools. Art imposes interfaces — ways of seeing, remembering, surprising — and technology provides the operational grammar. Every historical leap is an “update”: it’s not that technology creates art, nor that art simply springs from technique; rather, they provoke and update each other in a continuous loop.

Keeping memory alive is a technical challenge. Concrete, arches, roads, and aqueducts were not built for their own sake but to sustain collective images—power, worship, remembrance. Miniatures, manuscripts, and bookbindings pushed craftsmen to refine inks and supports; copying texts preserved both technical know-how and artistic practice. Cultural “software” and “hardware” evolve together: languages change, new mechanisms are invented to animate statues, curtains, and fountains. Art, driven by the desire to astonish, becomes a direct engine of engineering. Machines are not only built to save effort; they are built to create experience. It’s an early form of interaction design: the brief is to make the public feel; technology is the reply.

Temples, pyramids, churches arise from aesthetic intentions that demand engineering: volumes, proportions and light are conceived first, then mathematics and mechanics are called in to realize them. The pursuit of the “beautiful” is not mere decoration; it becomes a design constraint that pushes new materials and construction solutions. Beauty, in this sense, is functional: it communicates, and to communicate often requires novel techniques.

Art and technology develop memory and structure. Metaphor — alongside allegory and symbolism — becomes the pillar of artistic expression, just as material choices become the pillar of technology. From that moment on, humans refine the mechanisms they’ve discovered: technology turns needs into functional tools; art orders those needs into harmonious shapes that capture attention. Born of the same womb but carrying different genetic codes, they are, ultimately, twins different.

2- The Installed Software

Humans discover the potential of objects to become tools. This duality will prove to be the driving force of technological development — the same binary impulse that still shapes us today. From the use of pigmented stone on cave walls to the design of sacred spaces, aesthetic demands call for new construction techniques. Needs generate technical problems; art formulates the questions; technology supplies the solutions. Call this the primal paradigm that underpins human progress.

Early humans learned by experience and stored that knowledge in memory. When someone realised that memories could be transferred to a wall — using a branch dipped in pigment as a primitive pen — everything changed. That external record transformed private remembrance into a shared resource.

Cave painting shaped a mind only beginning to form its own self-awareness. People discovered that fixing needs and events into an external record helped cognition itself: it organised thought, made ideas clearer. It was the first “visual spreadsheet.” But inscribing an image was not enough; the image had to be composed. Key elements had to be selected, ordered, and given narrative sense. In short, invention met storytelling.

Aesthetic inquiry pushed beyond the cave. Metalwork demanded new technical leaps — alloys, casting, chiselling — while the need to register myths, accounts and sacred rites prompted the invention of writing. Writing is not merely a technique: it is a visual language that must be legible, reproducible and standardised. Technology enables the medium; art defines its grammar. Soon, sequence alone ceased to satisfy: events needed meaning. Thus, metaphor was born.

#1 The first steps

Art and technology are often perceived as distant realms: the former is the domain of expression of subjectivity; the latter is the realm of function and objectivity. And yet, from the very dawn of humanity, their histories have been deeply intertwined—like twin souls born from the same need: to survive and to remember. (Need: this concept will return and be expanded upon shortly.)

Early humans had to develop the rudiments of technology when they first felt the urge to crystallize memory. Faced with vast rock walls, primitive people began to feel the need to leave a mark, and so graffiti was born. That moment changed the course of human destiny. First, they had to craft tools to imprint what they had seen: their memories. Particularly hunting scenes. But why?

Hunting represents, more than any other event, the delicate balance between life and death. Life, because without it, there would be no food, and thus, death. But also because the hunt itself was deadly. And here, art took its first step. The first artist in history must have understood the importance of leaving a trace of these moments. And soon after, they had to find a technical solution to achieve their goal.

Thus, a stick, no longer seen as a mere natural object, was transformed into a functional tool.

And then came the ink (let’s call it that). Something that could last over on the rock. Early humans likely experimented with various clays and pigments, failing often before eventually discovering the right mixture. Up to this point, we might speak only of technique. But it soon became clear that technology alone would not be enough.

They had invented the hardware; now they needed the software.

It became apparent that memories could not be transferred in a raw, instinctive way. In transitioning from one medium to another, from visual memory to a physical surface, came the necessity to structure the memory itself. The language of memory was not the same as the language of representation. This marked the first true convergence of art and technology—each forced to interact with the other.

The mind arranges images in a disordered, fluid manner. But that same chaos, once transferred onto a static surface, no longer worked. So the elements had to be reordered, arranged so that even another human, someone without the same experience, could understand, follow, and interpret the story. So the art began to carve out its place in human society.

Once the technique was found, once humans discovered how to use it for their purpose, they began to make representations. But they didn’t stop there.

The spear had already reached a level of refinement that allowed it to perform its task. But hunting could not simply be about lunging at an animal. The strategy was essential. As far as we know, one common technique used for hunting mammoths involved herding them into dead-end paths and attacking from above and below with spears and stones. But with the arrival of rock-wall technology, many things changed.

The primitive humans now had to organize what they wanted to inscribe, to encode memory.

Representation alone was not enough. It was necessary to give meaning to the scene, to create a mechanism capable of burning that image into memory as vividly as possible. Depiction was not enough; it had to signify something. And this, as we later learned, would be called a metaphor.

Thus, the first key insight is that there could be no art without technology and no technology without art.

Humans began to walk with alternating steps—one artistic, one technological—as if to seal the fusion of the two worlds. To move forward together, ensuring the survival of both.

And of humankind itself.